Yet, Vietnamese career diplomat Le Luong Minh, who took

over the leadership of ASEAN last year, couldn’t help but disappoint

them because in many ways he represents much of what’s wrong with ASEAN

today.

ASEAN Secretary-General Minh opened with a speech that did

little to excite the audience. He focused on ASEAN’s 6 pillars when it

was formed in 1967 and its most ambitious project since then – creating

one regional economic grouping, the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC)

slated to come together by December 2015.

Someone asked about tensions between Australia and

Indonesia, ASEAN’s largest member, over asylum seekers and recent

wiretapping charges from NSA classified documents.

“I hope these bilateral issues can be resolved amicably,”

said ASEAN’s leader. “We have not seen any negative impact of that

bilateral relationship on the ASEAN-Australian partnership.”

On ASEAN’s most contentious issue – the conflict between

China and many ASEAN member countries in the South China Sea, Minh said,

“ASEAN is of the view that it needs to be resolved, but it can only be

resolved, and it should only be resolved, between the parties

concerned.”

Minh was safe, uninspiring and bureaucratic. ASEAN

insiders say it’s the luck of the draw, and that the rotating head of

ASEAN moves from a politician like former Thai Foreign Minister Surin

Pitsuwan, who can inspire outside interest, to a bureaucrat who can set

the ASEAN house in order like Minh. From 2004-2011, Minh was Vietnam’s

Permanent Representative to the United Nations while at times

concurrently his country's Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs.

Unfortunately, he's also ASEAN's least likely salesman.

Dynamic time

Yet, it’s an exciting and dynamic time when a single,

liberalized ASEAN could boost investments significantly. There’s also an

opportunity for ASEAN to provide much needed leadership at a time of

shifting geo-political power.

ASEAN is at a crossroads. Created at a time of global

dominance by the United States, times have changed - with economic power

shifting to China. Instead of taking leadership, ASEAN is in danger of

becoming a low-intensity proxy battlefield.

Nations like the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia are

unprepared for open conflict with China or even for negotiating with

China over the South China Sea. Many ASEAN nations turn to the United

States for defense support. At the same time, ASEAN’s poorer nations,

Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar, have become so dependent on China that

analysts call them “client states of Beijing.”

This leaves an opening for Australia, ASEAN’s 1st dialogue partner.

“ASEAN does have an

identity in Australian diplomacy, and it’s a positive one,” said Senator

Brett Mason, the Parliament Secretary to the Minister for Foreign

Affairs, who acknowledged the changing global power structures and

Australia’s shifting focus to Asia. “It’s a forum that could be used

more creatively and more fully, but I don’t think it’s ineffective.”

I’ve been reporting on ASEAN since 1987. I was there in

the late 1990s when Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar were admitted in

the grouping, creating a three-tiered system because these economies

lagged far behind original members Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, the

Philippines and even more affluent Brunei and Singapore.

Like many Asians, I hoped constructive engagement would be

a different way to push reforms, more effective than the

confrontational push from the West, but decades later, constructive

engagement remains an excuse – a failure of leadership. Reforms in

Myanmar, which was the main focus of constructive engagement, were

fueled by an internal process - with little help from ASEAN.

During the financial crisis of 1997, which started in

Thailand and spread to Indonesia, the nations turned, not to ASEAN, but

to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). When smog and haze from forest

fires in Indonesia that same year engulfed cities in Malaysia and

Singapore, ASEAN proved incapable of working together to prevent this

near-annual event that continues to plague the region today.

In 1999, ASEAN was criticized for failing to hold

Indonesia accountable for what was effectively a scorched earth policy

in East Timor. Leadership then came from Australia, which led INTERFET,

an international non-UN peacekeeping force.

In the late 2000s under pressure from some members, ASEAN

formed a human rights body that’s stayed largely silent on ongoing human

rights violations within ASEAN, like in Vietnam or the Rohingyas in

Myanmar.

Fissures over China

Dealing with China clearly shows the fissures inside

ASEAN. At the July, 2012 meeting in Cambodia, conflict erupted openly.

For the first time ever, the foreign ministers failed to agree on a

joint statement - with Filipino officials storming out of the meeting.

Other ASEAN states accused host Cambodia of working against ASEAN

interests by protecting China, Cambodia’s largest trading partner. Two

months later, Cambodia announced $500 million in new assistance from

China.

While largest nation and founding member Indonesia tried

to use shuttle diplomacy for a satisfactory agreement, ASEAN again fell

short of leadership.

Still, Australian officials seem optimistic.

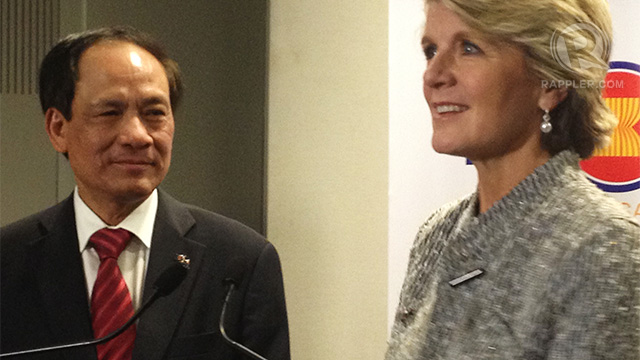

On March 19, Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop

hosted ASEAN’s Secretary-General Minh for the 40th anniversary of a

partnership she says now prioritizes trade, investment, regional

security and education.

40 YEARS. ASEAN Sec Gen Le Luong Minh with Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop

40 YEARS. ASEAN Sec Gen Le Luong Minh with Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop

“The extent of government contact – economic, financial –

really is at a much higher level now than a decade before that,” a

senior foreign affairs official told me. “Building ties just below the

political level, senior level official contact, over the last decade has

given our relationship a lot more ballast than ever before.”

The problem lies in two

areas: ASEAN makes decisions based on consensus, unwieldy in today’s

fast-moving world and in an organization that spans a wealth gap from

Singapore to Laos; and that wealth gap leads to differences in

leadership experience and style.

Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar tend to have fewer

officials capable of participating fully in meetings held in English.

The most progressive of these nations, Vietnam, used government money to

train a new generation of foreign service diplomats like Minh.

Consensus not enough

Still, the skills needed for consensus building are not

enough to inspire faith in the ASEAN way, and senior officials who have

led ASEAN, with few exceptions, have not had the charisma or status to

demand necessary meetings with heads of states.

In order to effectively push forward an ambitious ASEAN

agenda of one market, ASEAN must move faster, and its leader must lead –

not just within ASEAN but among its dialogue partners and potential

investors.

“While there’s so much criticism about ASEAN in terms of

leadership, ASEAN is all we have to work with,” said Deakin University’s

Dr. Sally Wood. “I don’t know if they ever really expected that they

would reach this level of centrality. There are so many contending

national interests in the region. So that makes it very challenging for

ASEAN to be able to speak with one voice.”

ASEAN Sec-Gen Minh is trying to fill a tall order, and

insiders say his experience is helping build the organization behind the

scenes. At ANU, he said he’s optimistic that the economic integration

of ASEAN, which promises a single market and a highly competitive

region, will happen as scheduled on December, 2015.

“ASEAN has implemented about 80% of all the measures,” he told the audience at ANU.

Not all agree.

“We’ve got to be realistic. I cannot see that this is

going to happen,” said Professor Andrew Walker, Acting Dean of ANU

College of Asia and the Pacific.

“It looks unlikely that AEC 2015 will be met,” added Wood.

“Perhaps it doesn’t matter that it won’t be realized in 2015, but that

ASEAN is working on it.” - Rappler.com

No comments:

Post a Comment